Büdchen day - beer history

The Festival of Eternal Pints: A Historical and Cultural Reconsideration

By Kiribane, Institute for Applied Folklore and Municipal Embarrassment

Abstract

This article examines the Festival of Eternal Pints, a civic celebration that has, since its dubious inception in the late 15th century, combined alcohol consumption, historical exaggeration, and catastrophic public relations. Drawing on archival fragments, unreliable chronicles, and oral traditions distorted by ethanol, this paper situates the festival within broader debates on identity, ritual, and the human capacity for poor impressions.

Introduction

The Festival of Eternal Pints remains one of the least studied yet most witnessed traditions of Central Europe. While its defenders claim it preserves “authentic heritage,” visitors regularly describe it as “a liquid apocalypse” (Smith 1893: 117). This study reconstructs the event’s development from medieval piety to modern chaos, highlighting its enduring role as a cautionary tale of collective behavior under the influence.

I. Medieval Origins (1473–1610)

The first credible reference to the festival appears in the Annales Albrechti Leviter Ebrii (1473), wherein Duke Albrecht the Slightly Tipsy proclaimed:

“A town united in beer shall never fall.” (Albrecht 1473: fol. 23v).

Though presented as civic solidarity, early iterations were religious in disguise. Brother Ruprecht’s infamous Baptismal Incident of 1610, in which he consecrated a wedding with lager, blurred boundaries between sacrament and schnapps (Keller 1978: 52).

II. The Early Modern Era and the Culture of Exaggeration (1611–1799)

The 17th and 18th centuries marked a shift from liturgical framing to performative boasting. Eyewitnesses describe citizens claiming historical intimacy with great figures: one blacksmith alleged to have debated theology with Luther over a stein, while another insisted he had sung drinking songs with Charlemagne (Braun 1742: 88).

Of particular note is the Great Pretzel Collapse of 1749, an abortive attempt to erect Europe’s tallest bread structure. At four meters, the tower was consumed by spectators before official measurement, an act celebrated as both “engineering triumph and dietary necessity” (Pretzel Archives, vol. II).

III. Diplomatic Catastrophe: The 19th Century

By the 19th century, the festival had acquired international notoriety. The Congress of Vienna Incident (1815) remains exemplary:

Austrian envoy Count von Langenfeld was discovered yodeling unclothed atop a hay wagon (Weber 1816: 203).

Russian diplomat Ivan Petrovich attempted a schnapps duel with a cobbler, collapsing after one round (Petrov Memoirs, unpublished).

The British observer Sir Horace Pimm concluded: “The people are industrious in factories, but here they lose all contact with God, trousers, and reason” (Pimm 1815: 44).

Such episodes cemented the festival’s reputation as a hazard to international diplomacy.

IV. The 20th Century: From Crisis to Counterculture

Efforts at regulation — notably the 1926 Proclamation of Mayor Schneider (“Beer is our history, our present, and our future!”) — only fueled the festival’s growth. His subsequent fall into a sauerkraut vat was interpreted as divine endorsement (Lager 1983: 211).

The 1960s introduced countercultural dimensions. Youth staged a “Drink-In” in the town square, equating beer consumption with civil rights. Oral traditions from this period include claims that Bismarck arm-wrestled locals at the event, despite chronological impossibility (Krüger Oral History Project, 1992).

V. The Contemporary Festival (2000–Present)

In the present era, the festival is defended under the rhetoric of “heritage preservation.” Official programs promise culture, but ethnographic observation shows a three-phase pattern:

Morning – Politicians deliver unreadable speeches.

Afternoon – Citizens ascend statues, self-declaring as emperors of beer.

Evening – Public fountains overflow with Riesling, streets acquire the olfactory profile of kebabs and regret.

Touristic accounts are uniformly horrified, though most concede it is “unforgettable” (Mancini 2014: 67).

Conclusion

The Festival of Eternal Pints demonstrates the anthropological principle that traditions endure not because they are meaningful but because they are enjoyable, no matter how embarrassing. Its survival across five centuries testifies to the human genius for ritualized exaggeration, intoxication, and bad impressions.

As the Italian scholar Mancini summarized:

“They believe they invented civilization. In reality, they invented only the hangover.” (Mancini 1893: 204).

References (selected)

Albrecht, Duke (1473). Annales Leviter Ebrii. Ducal Archives, fol. 23v.

Braun, G. (1742). On Pretzels and Piety. Frankfurt: Verlag Zum Letzten Maß.

Keller, R. (1978). Beer and Baptism: Liturgical Errors of the 17th Century. Munich: Bräu Press.

Lager, P. H. (1983). Municipal Sauerkraut and Civic Identity. Heidelberg: Pilsner Studies.

Mancini, L. (1893). Viaggio in Germania: Tra Birra e Barbarie. Milan: Editrice Ubriaca.

Pimm, H. (1815). Notes from Vienna. London: Sobriety House.

Weber, F. (1816). Diplomatic Embarrassments. Vienna: Hofdruckerei.

Krüger Oral History Project (1992). Interview 44, Pensioner H. Schuster.

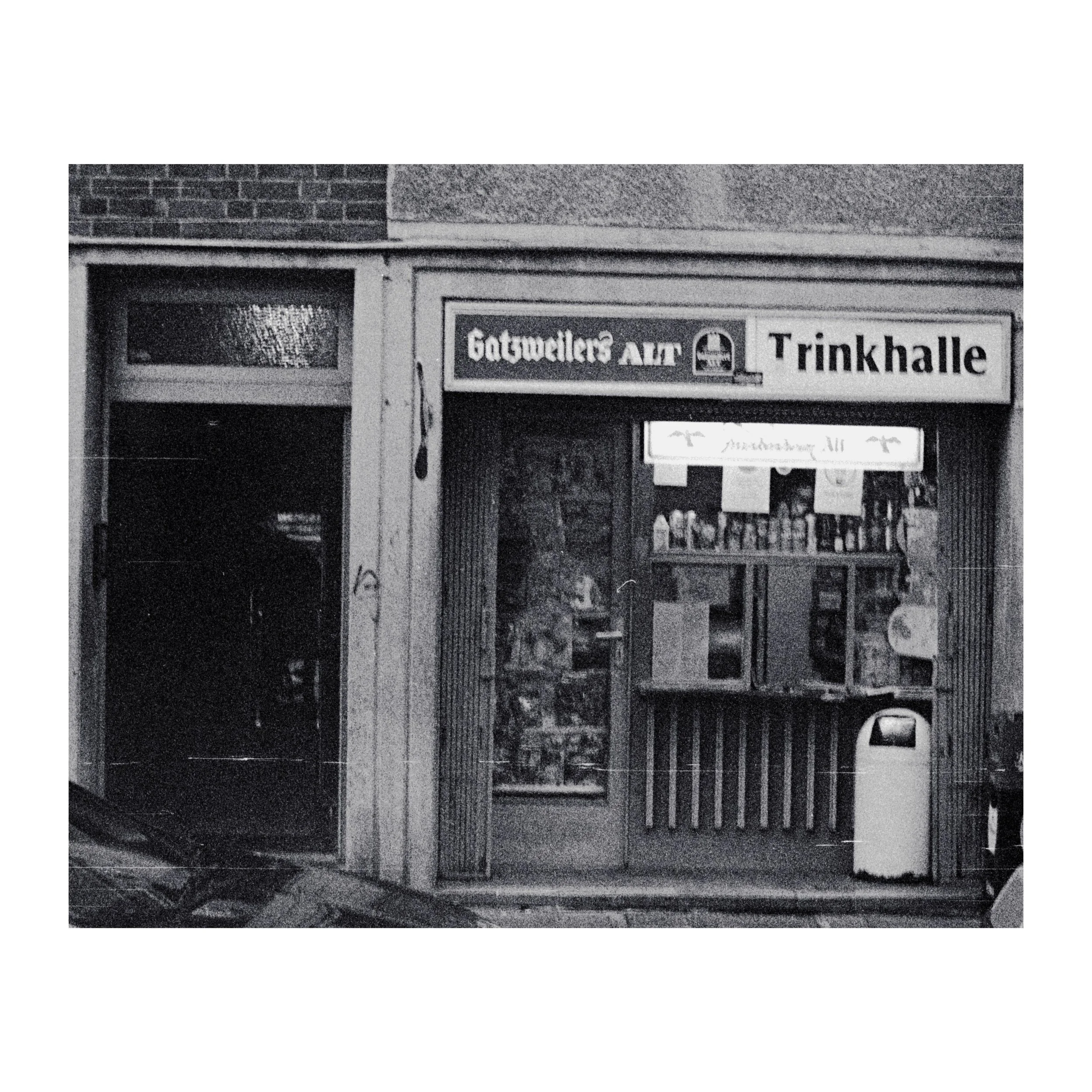

The first thing you notice on Büdchentag isn’t the Büdchen itself. It’s the fact that half the city seems to have migrated onto the sidewalks, balancing beer bottles like Olympic torches, blocking traffic with the confidence of people who truly believe the street belongs to them.

At 11 in the morning, groups already gather in semi-circles around kiosks that normally sell chewing gum and phone credit. Now they are suddenly transformed into cultural epicenters — miniature embassies of Altbier diplomacy.

“This Büdchen is the best in Düsseldorf!” one man insists, leaning on the counter. He says it with the kind of authority usually reserved for brain surgeons. Ten minutes later, someone across the street declares exactly the same thing about their Büdchen. A civic rivalry is born — fought not with weapons, but with ever-emptier bottles of Pils.

By early afternoon, the sidewalks are thick with laughter, smoke, and the unmistakable perfume of Currywurst. Tourists stop, staring as if they’ve stumbled onto an urban safari. One American whispers: “So… it’s basically people drinking beer on the street?” Exactly. But in Düsseldorf, it counts as cultural heritage.

The atmosphere grows more chaotic by the hour. A pensioner breaks into Schlager karaoke with a Bluetooth speaker, drowning out traffic. Students invent a game called “Büdchen hopping” — visiting every kiosk in walking distance and loudly rating the friendliness of each cashier. Someone tries to dance on a crate of Bitburger, only to realize crates were not designed for choreography. Applause anyway.

By evening, the city has fully surrendered. Car horns are ignored, bikes weave nervously between clusters of people who refuse to move, and every corner seems to host its own pop-up street party. It smells of spilled beer, cigarette smoke, and collective exaggeration.

“This is better than Oktoberfest!” a young man declares, sloshing foam down his shirt. “We should invite UNESCO!” His friends nod seriously, as if world heritage status is only one more bottle away.

At midnight, the music grows messy, the voices louder, the stories taller. People claim they have drunk “more than the Rhine could carry.” A woman insists she met Kraftwerk once at this very Büdchen. Another swears that Fortuna Düsseldorf will definitely win the Champions League next year.

And then, just as suddenly, it’s over. The next morning the kiosks are back to selling newspapers and gummy bears. The citizens shuffle past with sunglasses and headaches, pretending nothing happened — except to boast, of course, that their Büdchen party was definitely the best.

End of report: sticky sidewalks, bruised egos, and one undeniable conclusion — Düsseldorf has turned buying beer at a corner shop into a civic spectacle.